Dracula Bite comme des marques communautaires figuratives en couleurs

Tribunal EU 5 juin 2014, IEFbe 862, affaires T-495/12; T-496/12; T-497/12 (Dracula Bite) - dossier Marque communautaire. Un recours en annulation formé par le titulaire de la marque figurative nationale comportant l'élément verbal "Dracula", pour des produits et services des classes 33 et 35, contre la décision R 680/2011-4 de la quatrième chambre de recours de l'Office de l'harmonisation dans le marché intérieur (OHMI), du 6 septembre 2012, rejetant le recours introduit contre la décision de la division d'opposition qui refuse l'opposition introduite par la requérante à l'encontre de la demande d'enregistrement de la marque figurative en couleurs comportant les éléments verbaux "Dracula Bite", pour des produits et services des classes 33, 35 et 39. Les recours sont rejetés.

Marque communautaire. Un recours en annulation formé par le titulaire de la marque figurative nationale comportant l'élément verbal "Dracula", pour des produits et services des classes 33 et 35, contre la décision R 680/2011-4 de la quatrième chambre de recours de l'Office de l'harmonisation dans le marché intérieur (OHMI), du 6 septembre 2012, rejetant le recours introduit contre la décision de la division d'opposition qui refuse l'opposition introduite par la requérante à l'encontre de la demande d'enregistrement de la marque figurative en couleurs comportant les éléments verbaux "Dracula Bite", pour des produits et services des classes 33, 35 et 39. Les recours sont rejetés.

Lees verder

Demande d’enregistrement marque communautaire verbale FREELOUNGE

Tribunal EU 4 juin 2014, IEFbe 861, affaire T-161/12 (FreeLounge) - dossier Marque communautaire. Un recours en annulation formé par le titulaire des marques verbale et figurative, dénomination sociale et nom de domaine nationaux comportant les éléments verbaux "free LA LIBERTÉ N’A PAS DE PRIX", "FREE" et "FREE.FR", pour des produits et services classés dans les classes 9 et 38, contre la décision de la chambre de recours de l'OHMI annulant partiellement la décision de la division d'opposition qui refuse la demande d'enregistrement de la marque verbale "FreeLounge", pour des produits et services classés dans les classes 16, 35 et 41, dans le cadre de l'opposition introduite par la requérante. Le recours est rejeté pour le surplus.

Marque communautaire. Un recours en annulation formé par le titulaire des marques verbale et figurative, dénomination sociale et nom de domaine nationaux comportant les éléments verbaux "free LA LIBERTÉ N’A PAS DE PRIX", "FREE" et "FREE.FR", pour des produits et services classés dans les classes 9 et 38, contre la décision de la chambre de recours de l'OHMI annulant partiellement la décision de la division d'opposition qui refuse la demande d'enregistrement de la marque verbale "FreeLounge", pour des produits et services classés dans les classes 16, 35 et 41, dans le cadre de l'opposition introduite par la requérante. Le recours est rejeté pour le surplus.

42. Du fait de l’erreur d’appréciation identifiée au point 31 ci-dessus, la chambre de recours ne s’est en revanche pas prononcée sur la question de savoir si la similitude existant entre les services relevant de la classe 41 visés par la demande d’enregistrement, d’une part, et les services de diffusion d’informations par voie électronique pour les réseaux de communication mondiale de type Internet couverts par la marque figurative antérieure, d’autre part, présentait un degré plus ou moins élevé.

Inbreuk op verbeterd aerosol spuitbus ventiel

Rechtbank van Koophandel Gent 5 juni 2014, IEFbe 858 (Clayton tegen A) Uitspraak ingezonden door Steven Cattoor, Hoyng Monegier LLP. Octrooirecht. Gerechtelijke recht. Verhouding EOB-oppositie. Clayton is houdster van EP 1 789 343 voor een 'Verbeterd aerosol spuitbus ventiel' en vordert inbreukstaking. A vordert nietigverklaring van Belgische luik en verzoekt dat de zaak geschorst zou worden totdat het EOB uitspraak zal hebben gedaan omtrent de door haar ingestelde oppositie. De rechtbank oordeelt het opportuun om de nietigheidsvordering op te schorten hangende de oppositie, en verzoekt het EOB per brief om de deze versneld te behandelen.

Uitspraak ingezonden door Steven Cattoor, Hoyng Monegier LLP. Octrooirecht. Gerechtelijke recht. Verhouding EOB-oppositie. Clayton is houdster van EP 1 789 343 voor een 'Verbeterd aerosol spuitbus ventiel' en vordert inbreukstaking. A vordert nietigverklaring van Belgische luik en verzoekt dat de zaak geschorst zou worden totdat het EOB uitspraak zal hebben gedaan omtrent de door haar ingestelde oppositie. De rechtbank oordeelt het opportuun om de nietigheidsvordering op te schorten hangende de oppositie, en verzoekt het EOB per brief om de deze versneld te behandelen.

De inbreukvordering kan volgens de rechtbank evenwel niet geschorst worden nu dit de beschermingsduur van het octrooi volledig zou uithollen en vooralsnog niet werd aangetoond dat het zeer waarschijnlijk zou zijn dat de oppositie zal slagen. Vervolgens oordeelt de rechtbank dat aerosolventielen en spuitbuskleppen vervaardigd uit een glasgevulde polyolefine met glasinhoud tussen 3% en 30% of enkele tienden van een procent buiten deze marge een inbreuk uitmaken op het octrooi van Clayton.

Het beweerde recht op persoonlijk voorgebruik wordt afgewezen, en een deskundigenonderzoek wordt bevolen om de rechtbank bij te staan in de schadebegroting. Clayton kan volgens de rechtbank tenslotte geen aanspraak maken op een “redelijke vergoeding” onder Art. 67(3) EOV en Art. 29 BOW (toepassing van de uitvinding hangende de aanvraag, voorafgaand aan de verlening) nu de nodige vertaling niet werd neergelegd of aan A meegedeeld, en het in elk geval niet bewezen wordt geacht dat A van de octrooiaanvraag op de hoogte was.

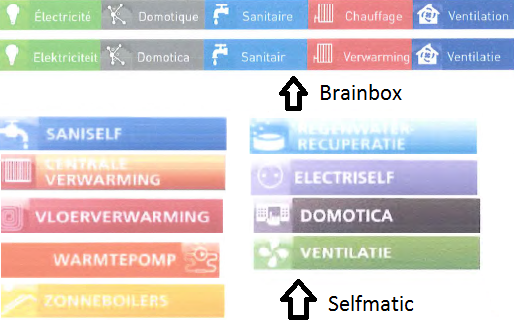

Adaptaties van assortimentenlogo's en voorpagina zelfbouwcatalogus

Voorz. Rechtbank van Koophandel Brussel 26 februari 2014 , IEFbe 857 (Brainbox tegen Selfmatic)

Auteursrecht. Inbreuk door adaptatie. Parasitisme/kielzogvaren. Misleidende reclame. Staking. Geen publicatiebevel. Brainbox en Selfmatic zijn actief in de sector van de zelfbouwsystemen. In de cataloog van Brainbox worden assortimentenlogo's gebruikt. Selfmatic gebruikt soortgelijke logo's. De voorpagina van de catalogus vertonen ook gelijkenissen. Het gebruik door Selfmatic, zonder toestemming van de auteur, van adaptaties van de vierkante Brainbox-pictogrammen en de voorpagina van de Brainbox-cataloog zijn inbreuken op de auteursrechten. Het weglaten van pictogrammen volstaat niet om een inbreuk te omzeilen. Er is sprake van parasitaire mededinging én misleidende reclame (95 én 96 WMPC). De gevorderde publiciteitsmaatregelen zijn niet om bij te dragen aan de stopzetting van de inbreuk. Status: hoger beroep werd ingesteld.

Auteursrecht. Inbreuk door adaptatie. Parasitisme/kielzogvaren. Misleidende reclame. Staking. Geen publicatiebevel. Brainbox en Selfmatic zijn actief in de sector van de zelfbouwsystemen. In de cataloog van Brainbox worden assortimentenlogo's gebruikt. Selfmatic gebruikt soortgelijke logo's. De voorpagina van de catalogus vertonen ook gelijkenissen. Het gebruik door Selfmatic, zonder toestemming van de auteur, van adaptaties van de vierkante Brainbox-pictogrammen en de voorpagina van de Brainbox-cataloog zijn inbreuken op de auteursrechten. Het weglaten van pictogrammen volstaat niet om een inbreuk te omzeilen. Er is sprake van parasitaire mededinging én misleidende reclame (95 én 96 WMPC). De gevorderde publiciteitsmaatregelen zijn niet om bij te dragen aan de stopzetting van de inbreuk. Status: hoger beroep werd ingesteld.

Auteursrecht

p. 10: "Brainbox voert terecht aan dat de originaliteit van haar assortimentenlogo's voortvloeit uit een combinatie van volgende elementen:

- De oorspronkelijke vierkanten assortimentenlogo's (...), gekenmerkt door:

- een hoekig vierkant gekleurd vlakje

- met daarin een boog die gevormd wordt door de scheiding tussen nuances (licht versus donker) van de assortiment-kleur;

- met daarin een pictogram in het wit voor de aanduiding van een productenassortiment door middel van een symbool

- met daarin een aanduiding van het betreffende assortiment eveneens in witte letters."

p. 11: "De originaliteit van de voorpagina van de Brainbox-cataloog (2012; 2013), en de advertentie in "Ik Ga Bouwen 2012", bestaat uit het gebruik van:

- een foto die een lachend jong koppel toont in een werfsfeer

- die op de achtergrond een venster toont

- waarvan de dominante kleuren wit en (licht-)grijs zijn

- afgeboord met een veelkleurige band

- bestaande vier aaneensluitende, gekleurde, rechthoekige vlakken (...) om de assortimenten aan te prijzen "

P. 13 "Indien een werk opvallend veel gelijkenissen vertoont met een eerder bestaand werk, moet nagegaan worden of deze gelijkenissen met het oudere werk toevallig zijn, dan wel voorkomen uit bewuste of onbewuste ontlening aan dat werk en aldus inbreuk wordt gemaakt op het auteursrecht."

P. 16: "In casu is er sprake van parasitaire mededinging of aanhaking, gelet op:

- (...) [95 WMPC]

Misleidende reclame: gelet op de gelijkenissen met de Brainbox - vormgeving creëert de gewraakte Selfmatic publiciteit verwarringsgevaar bij een gemiddelde consument (een publiek met gemiddelde aandacht) en kan zij hem misleiden nopens de oorsprong van de aangeboden producten.

Maatregelen:

De opgelegde staking moet voldoende zijn om de inbreuken op het auteursrecht van Brainbox stop te zetten. De gevorderde publiciteitsmaatregelen zijn niet van aard om op een efficiënte wijze aan de stopzetting van de inbreuk bij te dragen.

Prejudiciële vragen over beschrijvende, grafische voorstelling van afwezige ingrediënten

Prejudiciële vraag HvJ EU 26 februari 2014, IEFbe 856, zaak C-195/14 (Teekanne) - dossier

Reclamerecht. Etikettering. Verzoekster handelt in thee. Zij verhandelt onder de naam „Felix Himbeer Vanille Abenteuer” een vruchtenthee, met een verpakking waarop afbeeldingen van frambozen en vanillebloesems staan en de aanduidingen „nur natürliche Zutaten”en „Früchtetee mit natürlichen aromen” terwijl in werkelijkheid deze thee geen bestanddelen of aroma’s van vanille of frambozen bevat. Gestelde vraag: “Mogen de etikettering en presentatie van levensmiddelen alsmede de daarvoor gemaakte reclame door het voorkomen, de beschrijving of de grafische voorstelling, de indruk wekken dat een bepaald ingrediënt aanwezig is, terwijl dit ingrediënt in werkelijkheid ontbreekt, en dit enkel blijkt uit de lijst van ingrediënten overeenkomstig artikel 3, lid 1, punt 2, van richtlijn 2000/13/EG?”

Reclamerecht. Etikettering. Verzoekster handelt in thee. Zij verhandelt onder de naam „Felix Himbeer Vanille Abenteuer” een vruchtenthee, met een verpakking waarop afbeeldingen van frambozen en vanillebloesems staan en de aanduidingen „nur natürliche Zutaten”en „Früchtetee mit natürlichen aromen” terwijl in werkelijkheid deze thee geen bestanddelen of aroma’s van vanille of frambozen bevat. Gestelde vraag: “Mogen de etikettering en presentatie van levensmiddelen alsmede de daarvoor gemaakte reclame door het voorkomen, de beschrijving of de grafische voorstelling, de indruk wekken dat een bepaald ingrediënt aanwezig is, terwijl dit ingrediënt in werkelijkheid ontbreekt, en dit enkel blijkt uit de lijst van ingrediënten overeenkomstig artikel 3, lid 1, punt 2, van richtlijn 2000/13/EG?”

Verweerder is het Bundesverband der Verbraucherzentralen und Verbraucherverbände – Verbraucherzentrale Bundesverband; hij stelt dat de op de verpakking gegeven informatie misleidend is. Hij eist dat verzoekster een verbod wordt opgelegd op deze wijze reclame te maken, en een schadevergoeding voor de gemaakte aanmaningskosten van € 200.

In eerste instantie wordt verweerder in het gelijk gesteld, maar in beroep wordt die uitspraak vernietigd. De beroepsrechter is van oordeel dat geen sprake is van misleiding in de zin van de DUI wet inzake oneerlijke mededinging in samenhang met het DUI wetboek inzake levensmiddelen, consumptiegoederen en diervoeder. Uit de op de verpakking aangebrachte lijst van ingrediënten zou voor de redelijk geïnformeerde, omzichtige en oplettende gemiddelde consument voldoende duidelijk blijken dat de gebruikte aroma’s niet uit frambozen en vanille zijn gewonnen, maar enkel deze smaak hebben.

De zaak ligt nu voor ‘Revision’ bij de verwijzende DUI rechter (Bundesgerichtshof). Hij vraagt zich af of het voldoende is dat de indruk wordt gewekt dat een bepaald ingrediënt aanwezig is, terwijl dit ingrediënt in werkelijkheid ontbreekt, en dit enkel blijkt uit de lijst van ingrediënten overeenkomstig artikel 3, lid 1, punt 2, van richtlijn 2000/13/EG. Hij stelt daartoe de volgende vraag:

“Mogen de etikettering en presentatie van levensmiddelen alsmede de daarvoor gemaakte reclame door het voorkomen, de beschrijving of de grafische voorstelling, de indruk wekken dat een bepaald ingrediënt aanwezig is, terwijl dit ingrediënt in werkelijkheid ontbreekt, en dit enkel blijkt uit de lijst van ingrediënten overeenkomstig artikel 3, lid 1, punt 2, van richtlijn 2000/13/EG?”

HvJ EU: Browsen valt onder tijdelijke-kopie exceptie

HvJ EU 5 juni 2014, IEFbe 854, zaak C-360/13 (Public Relations Consultants Association tegen Newspaper Licensing Agency) - dossier

Auteursrecht. Reproductierecht. Tijdelijke reproductie. Zie eerder IEF 12948. Uitlegging van artikel 5, lid 1, van (InfoSoc-richtlijn 2001/29/EG). Beperkingen en uitzonderingen op reproductierecht. Begrip „tijdelijke reproductiehandelingen die van voorbijgaande of incidentele aard zijn en die een integraal en essentieel onderdeel vormen van een technisch procedéˮ. Kopie van webpagina die automatisch in het cache-internetgeheugen wordt opgeslagen en op het scherm wordt weergegeven. HvJ EU verklaart voor recht:

Auteursrecht. Reproductierecht. Tijdelijke reproductie. Zie eerder IEF 12948. Uitlegging van artikel 5, lid 1, van (InfoSoc-richtlijn 2001/29/EG). Beperkingen en uitzonderingen op reproductierecht. Begrip „tijdelijke reproductiehandelingen die van voorbijgaande of incidentele aard zijn en die een integraal en essentieel onderdeel vormen van een technisch procedéˮ. Kopie van webpagina die automatisch in het cache-internetgeheugen wordt opgeslagen en op het scherm wordt weergegeven. HvJ EU verklaart voor recht:

Artikel 5 van InfoSoc-richtlijn 2001/29/EG moet aldus worden uitgelegd dat kopieën op het computerscherm van de gebruiker en kopieën in het internetcachegeheugen van de harde schijf van die computer die door een eindgebruiker bij het raadplegen van een internetsite worden gemaakt, voldoen aan de voorwaarden tijdelijk te zijn, van voorbijgaande of incidentele aard te zijn en een integraal en essentieel onderdeel te vormen van een technisch procedé, alsook aan de voorwaarden van artikel 5, lid 5, van die richtlijn, en derhalve zonder toestemming van de houders van auteursrechten mogen worden gemaakt.

Gestelde vragen:

In omstandigheden waarin:

1. een eindgebruiker een webpagina bekijkt zonder deze pagina te downloaden, te printen of op enige ander wijze een kopie ervan te maken;

2. kopieën van deze webpagina automatisch op het scherm verschijnen en in het cache-internetgeheugen van de harde schijf van de computer van de eindgebruiker worden opgeslagen;

3. het maken van deze kopieën noodzakelijk is voor het technische procedé dat correct en doeltreffend surfen op het internet mogelijk maakt;

4. de op het scherm weergegeven kopie aldaar blijft staan tot de eindgebruiker de betrokken pagina verlaat, en zij dan ingevolge de normale werking van de computer automatisch wordt gewist;

5. de in het cachegeheugen opgenomen kopie aldaar blijft opgeslagen tot zij door andere gegevens wordt verdrongen doordat de eindgebruiker andere webpagina’s bekijkt, en zij dan ingevolge de normale werking van de computer automatisch wordt gewist;

6. de kopieën slechts worden bewaard voor de duur van de gewone procedés die met het sub (iv) en (v) hierboven beschreven internetgebruik gepaard gaan;

zijn dergelijke kopieën dan (i) tijdelijk, (ii) van voorbijgaande of incidentele aard, en (iii) vormen zij een integraal en essentieel onderdeel van het technische procedé in de zin van artikel 5, lid 1, van richtlijn 2001/29/EG1 ?

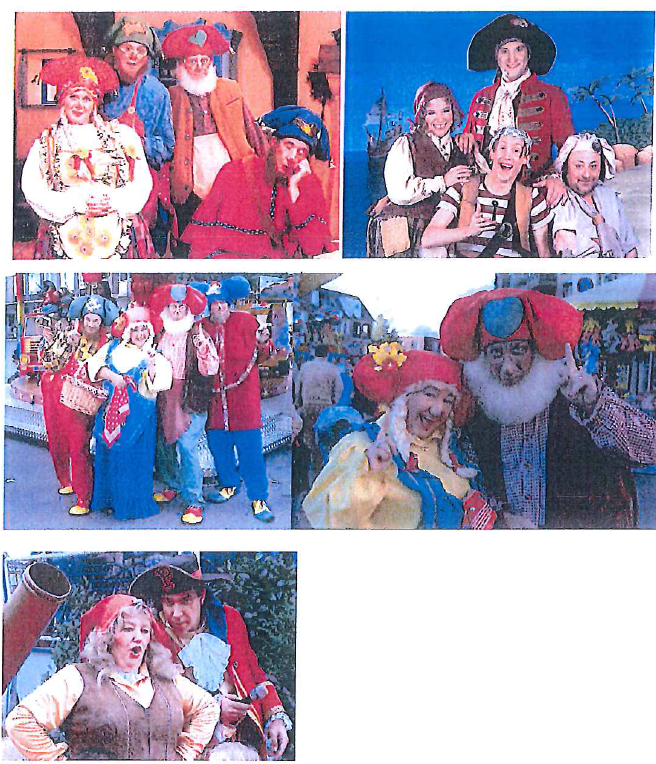

Kabouter Plop en Piet Piraat beschermen hun karakters

Rechtbank Amsterdam 4 juni 2014, IEFbe 854 (Studio100 tegen Vrolijke Kabouters-Pret Piraat)

Uitspraak ingezonden door Natalie van der Laan en Anne Voerman, DLA Piper. Studio100 exploiteert de karakters Kabouter Plop en Piet Piraat. Gedaagden treden op als lookalike onder de namen de Vrolijke Kabouters en Pret Piraat. De combinatie van elementen in de characters en de wijze waarop deze worden gepresenteerd genieten auteursrechtelijke bescherming, waarop inbreuk wordt gemaakt. Geen inbreuk op woordmerk Kabouter Plop als derden dat teken gebruiken voor aankondigingen. Tussen PRET en PIET PIRAAT is een grote visuele en auditieve overeenstemming. Door het gedogen gedurende vijf opeenvolgende jaren is ex 2.4 sub f BVIE geen merkrecht verkregen als dat te kwader trouw is verricht. PRET PIRAAT wordt nietig verklaard en er moet informatie over optredens en boekingen worden gegeven.

Uitspraak ingezonden door Natalie van der Laan en Anne Voerman, DLA Piper. Studio100 exploiteert de karakters Kabouter Plop en Piet Piraat. Gedaagden treden op als lookalike onder de namen de Vrolijke Kabouters en Pret Piraat. De combinatie van elementen in de characters en de wijze waarop deze worden gepresenteerd genieten auteursrechtelijke bescherming, waarop inbreuk wordt gemaakt. Geen inbreuk op woordmerk Kabouter Plop als derden dat teken gebruiken voor aankondigingen. Tussen PRET en PIET PIRAAT is een grote visuele en auditieve overeenstemming. Door het gedogen gedurende vijf opeenvolgende jaren is ex 2.4 sub f BVIE geen merkrecht verkregen als dat te kwader trouw is verricht. PRET PIRAAT wordt nietig verklaard en er moet informatie over optredens en boekingen worden gegeven.

4.9. Niet ter discussie staat dat Studio 100 bevoegd is op te komen tegen inbreuken op de woordmerken KABOUTER PLOP en PIET PIRAAT. Van een inbreuk op het woordmerk KABOUTER PLOP door gedaagde is evenwel niet gebleken. Gesteld noch gebleken is dat gedaagde zelf dit woordmerk heeft gebruikt. Dat derden onder de naam Kabouter Plop hebben aangekondigd, maakt niet dat dit gebruik aan gedaagde kan worden toegekend. Dit geldt temeer, nu gedaagde onbetwist heeft aangevoerd dat zij in de algemene voorwaarden die zij bij de optredens hanteert heeft opgenomen dat zij als de Vrolijke Kabouters aangekondigd dient te worden.

4.12. Op grond van artikel 2.4 sub f BVIE wordt er geen recht op een merk verkregen door de inschrijving van een merk waarvan het depot te kwader trouw is verricht. Naar het oordeel van de rechtbank is daarvan in dit geval sprake. De rechtbank neemt als vaststaand aan dat gedaagde op de hoogte was van het gebruik van het woordmerk PIET PIRAAT in de periode van drie jaar voorafgaand aan haar depot, nu dit niet door haar is betwist. Het televisieprogramma rond Piet Piraat wordt bovendien al sinds december 2001 uitgezonden en geniet grote bekendheid, ook in Nederland. Gedaagde heeft haar verweer, dat zij het merk PRET PIRAAT al sinds 2001 gebruikt op geen enkele wijze onderbouwd, zodat de rechtbank daaraan voorbij gaat. Dat zij al in 2001 kleding voor het character Pret Piraat heeft aangeschaft, duidt immers niet op gebruik als woordmerk. Dit betekent dat Studio 100 met recht de nietigheid inroept van de inschrijving van het merk PRET PIRAAT.

Conclusions de l’AG: Les bibliothèques peuvent mettre des livres à disposition sur support électronique

Conclusions AG HvJ EU 5 juin 2014, IEFbe 853, l'affaire C-117/13 (TU Darmstadt) - dossier  Auteursrecht. Reproductie. Digitaliseren. IEFbe 294. Interprétation de l'article 5, par. 3, sous n), de la directive INFOSOC 2001/29/CE. Exceptions et limitations aux droits de reproduction et de communication en cas d'utilisation à des fins de recherches et d'études privées. Livre mis à disposition, au moyen de terminaux spécialisés, à des particuliers dans une bibliothèque universitaire. Situation dans laquelle ledit livre peut être imprimé ou téléchargé vers une clé USB.

Auteursrecht. Reproductie. Digitaliseren. IEFbe 294. Interprétation de l'article 5, par. 3, sous n), de la directive INFOSOC 2001/29/CE. Exceptions et limitations aux droits de reproduction et de communication en cas d'utilisation à des fins de recherches et d'études privées. Livre mis à disposition, au moyen de terminaux spécialisés, à des particuliers dans une bibliothèque universitaire. Situation dans laquelle ledit livre peut être imprimé ou téléchargé vers une clé USB.

Communiqué de presse: Selon l’avocat général Niilo Jääskinen, un État membre peut autoriser les

bibliothèques à numériser, sans l’accord des titulaires de droits, des livres qu’elles détiennent dans leur collection pour les proposer sur des postes de lecture électronique. Si la directive sur le droit d’auteur ne permet pas aux États membres d’autoriser les utilisateurs à stocker sur une clé USB le livre numérisé par la bibliothèque, elle ne s’oppose pas, en principe, à une impression du livre à titre de copie privée.

Conclusie AG:

1) L’article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la [InfoSoc-directive 2001/29/CE], doit être interprété en ce sens qu’une œuvre n’est pas soumise à des conditions en matière d’achat ou de licence, lorsque le titulaire du droit offre aux établissements visés dans cette disposition de conclure à des conditions adéquates des contrats de licence d’utilisation de cette œuvre.

2) L’article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la directive 2001/29, interprété à la lumière de l’article 5, paragraphe 2, sous c), de ladite directive, ne s’oppose pas à ce que les États membres accordent aux établissements visés dans cette disposition le droit de numériser les œuvres de leurs collections, si la mise à la disposition du public au moyen de terminaux spécialisés le requiert.

3) Les droits prévus par les États membres conformément à l’article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la directive 2001/29 ne permettent pas aux usagers des terminaux spécialisés d’imprimer sur papier ou de stocker sur une clé USB les œuvres qui y sont mises à leur disposition.

Questions:

1. Une œuvre est-elle soumise à des conditions en matière d'achat ou de licence, au sens de l'article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la directive 2001/29/CE , lorsque le titulaire du droit offre aux établissements visés dans cette disposition de conclure à des conditions adéquates des contrats de licence d'utilisation de cette œuvre ?

2. L'article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la directive 2001/29/CE habilite-t-il les États membres à accorder aux établissements le droit de numériser les œuvres de leurs collections si la mise à disposition de ces œuvres au moyen de terminaux le requiert ?

3. Les droits prévus par les États membres conformément à l'article 5, paragraphe 3, sous n), de la directive 2001/29/CE peuvent-ils aller jusqu'à permettre aux usagers des terminaux d'imprimer sur papier ou de stocker sur une clef USB les œuvres qui y sont mises à leur disposition ?

BBIE mei/OBPI mai 2014

Merkenrecht. We beperken ons tot een maandelijks overzicht van de oppositiebeslissingen van het BBIE. Recentelijk heeft het BBIE een serie van 12 oppositiebeslissingen gepubliceerd die wellicht de moeite waard is om door te nemen. Zie voorgaand bericht in deze serie: BBIE-serie april 2014.

Merkenrecht. We beperken ons tot een maandelijks overzicht van de oppositiebeslissingen van het BBIE. Recentelijk heeft het BBIE een serie van 12 oppositiebeslissingen gepubliceerd die wellicht de moeite waard is om door te nemen. Zie voorgaand bericht in deze serie: BBIE-serie april 2014.

20-05 | BOSCH | BOSCH INVEKA | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

13-05 | ISIFIX | EASYFIKS | Afgew. | nl | ||

13-05 | Thalia | INFOTALIA THE CONTENT PORTAL | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

13-05 | KIKO | KIKAIS | Toegew. | nl |

13-05 | Thalia | INFOTALIA | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

12-05 | KENZO | ENZO label | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

12-05 | GREENPROOF GROENDAK GROEP | GREEN ROOF | Afgew. | fr | ||

09-05 | FARAH | FARAH&COCO | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

08-05 | VION | ZIVION | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

08-05 | ETRO | LUCIANO CAMELLI | Afgew. | fr | ||

08-05 | VG | VG | Gedeelt. | nl | ||

05-05 | BUGABOO | BUGABOO | Gedeelt. | nl |

Behoefte aan een verdere analyse? Tip de redactie: redactie@ie-forum.be

Nécessité d'une analyse plus approfondie? Note aux rédacteurs: redactie@ie-forum.be

Facturen en catalogi leveren bewijs tegen non-usus van SENSUS

OHIM 30 mei 2014, IEF 13906 (Swiss Sense tegen Rectitel)

Beslissing ingezonden door Gert Jan van de Kamp, Park Legal. Merkenrecht. Non-usus deels aangenomen. Swiss Sense roept ingevolge artikel 51 lid 1 onder a Gemeenschapsmerkenverordening (non-usus) het verval in van Gemeenschapsmerk SENSUS van Recticel. Het OHIM, onder verwijzing naar onder meer het arrest C-12/12 [IEF 12574](SM Jeans/Levi’s), oordeelt dat Recticel normaal gebruik heeft gemaakt van haar Gemeenschapsmerk SENSUS voor onder meer matrassen, matrasvullingen en hoofdkussens. De door Recticel overlegde facturen en catalogi leveren bewijs van (normaal) merkgebruik op voor onder andere Nederland, België, Luxemburg, Zweden en Frankrijk. Voor andere producten in de klassen 10, 17 en 20 volgt gedeeltelijk de nietigverklaring van het merk.

Beslissing ingezonden door Gert Jan van de Kamp, Park Legal. Merkenrecht. Non-usus deels aangenomen. Swiss Sense roept ingevolge artikel 51 lid 1 onder a Gemeenschapsmerkenverordening (non-usus) het verval in van Gemeenschapsmerk SENSUS van Recticel. Het OHIM, onder verwijzing naar onder meer het arrest C-12/12 [IEF 12574](SM Jeans/Levi’s), oordeelt dat Recticel normaal gebruik heeft gemaakt van haar Gemeenschapsmerk SENSUS voor onder meer matrassen, matrasvullingen en hoofdkussens. De door Recticel overlegde facturen en catalogi leveren bewijs van (normaal) merkgebruik op voor onder andere Nederland, België, Luxemburg, Zweden en Frankrijk. Voor andere producten in de klassen 10, 17 en 20 volgt gedeeltelijk de nietigverklaring van het merk.

Place of use:

“The evidence shows that the place of use has been different member countries of the European Union. This can be inferred from, for example, the invoices, which are submitted to customers in Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden and France. Furthermore, the product catalogues are issued for the public in Benelux, which is indicated for example by the web address www.beka.be, which can be seen in the catalogues. Consequently, as the use has been clearly shown in different member countries of the European Union, it is concluded that the evidence of use filed by the proprietor contains sufficient indications concerning the place of use.”

Nature of use:

“(...)The Cancellation Division also notices that the contested CTM is used together with other trade marks, such as “UBICA” or “BEKA”. However, there is no legal precept in the Community trade mark system which obliges the proprietor to provide evidence of the earlier mark alone when genuine use is required. Two or more trade marks may be used together in an autonomous way, with or without the company name, without altering the distinctive character of the earlier registered trade mark. The Court has confirmed that the condition of genuine use of a registered trade mark may be satisfied both where it has been used as part of another composite mark or when it is used in conjunction with another mark, even if the combination of marks is itself registered as a trade mark (judgment of 18/04/2013, C-12/12, ‘SM JEANS/LEVI’S’, para 36).”

Global assessment:

“When reviewing the evidence in its entirety, especially taking into account the invoices during the relevant time period and the fact that they indicate the economic extent of use relating to the genuine use of the earlier trade mark in part of the relevant market, it is considered that the evidence shows use of the earlier trade mark to a sufficient extent. This finding is supported by the evidence showing the catalogues of the products (indicating the nature of the use). “